Ever New, Ever Ancient

We tend to locate innovation in the output, the new product, or the finished piece of art. This is sometimes called revolutionary, breakthrough, or disruptive!

But long-term value lives elsewhere. Long-term value is endurance. It comes from what we keep doing: the craft, the process, the maintenance. It’s evolutionary!

A simple analogy (from the book Breakneck by Dan Wang): the dish isn’t the innovation; it’s the outcome. The innovation is the input: the kitchen tools, the recipe, and the practice of cooking well every time.

You see this product/process concept in other places beyond the kitchen. Below are some related thoughts:

++++

China’s Factory vs. Silicon Valley’s Lab

The same book, Breakneck, mentions that Andy Grove once warned the United States must “focus less on the mythical moment of creation” and more on scaling because when invention is separated from production, technology ecosystems rust.

In Silicon Valley, innovation is a novelty, a moment (we all remember the iPhone launch). That is the dish.

In China, it’s a process, a system of reproducibility. The dense network of engineers, suppliers, and factories? Those are the recipes and the kitchen tools.

Single innovation in a lab without a learning loop from the production process goes nowhere.

When Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin in 1928, it was a breakthrough. What changed the world wasn’t Fleming’s Petri dish; it was the process that came later. During World War II, scientists and engineers learned how to mass-produce penicillin, turning a fragile mold into an industrial medicine. The discovery was the spark. But the process, scaling, refining, and reproducing, was the revolution (where the value happened).

++++

“Low-road” vs. “High-road” Buildings

Just like technologies must learn production, buildings must learn construction. From Breakneck to Simon Leys’s The Hall of Uselessness to Stewart Brand’s How Buildings Learn, a similar idea surfaces.

Builders everywhere have attempted to overcome the erosion of time. Ancient Egypt and medieval Europe built great pyramids and cathedrals out of stone: the “high road.” These buildings were designed to project permanence, to stand against time itself. But rigidity is a kind of fragility. When Notre-Dame burned in 2019, the world realized how little of the medieval process survived. Western permanence preserved the object but lost the method.

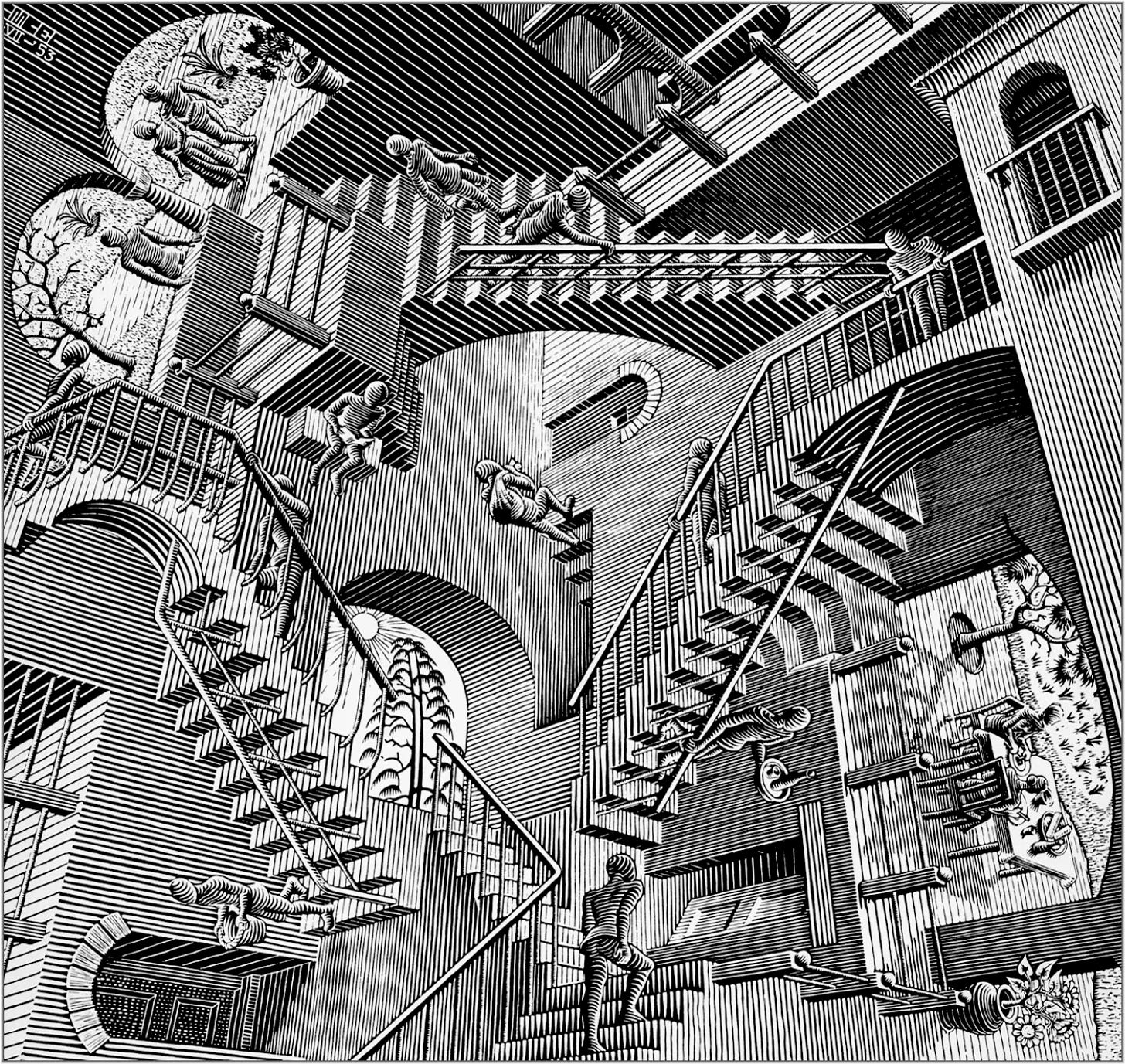

The “low road,” as Brand describes it, is the opposite approach: modest, flexible, easy to repair or rebuild. It prizes adaptability over monumentality. Japan’s Ise Grand Shrine has been rebuilt every twenty years for over a millennium, a structure that survives precisely because it is dismantled.

++++

Another way to think about this is in terms of development vs. maintenance.

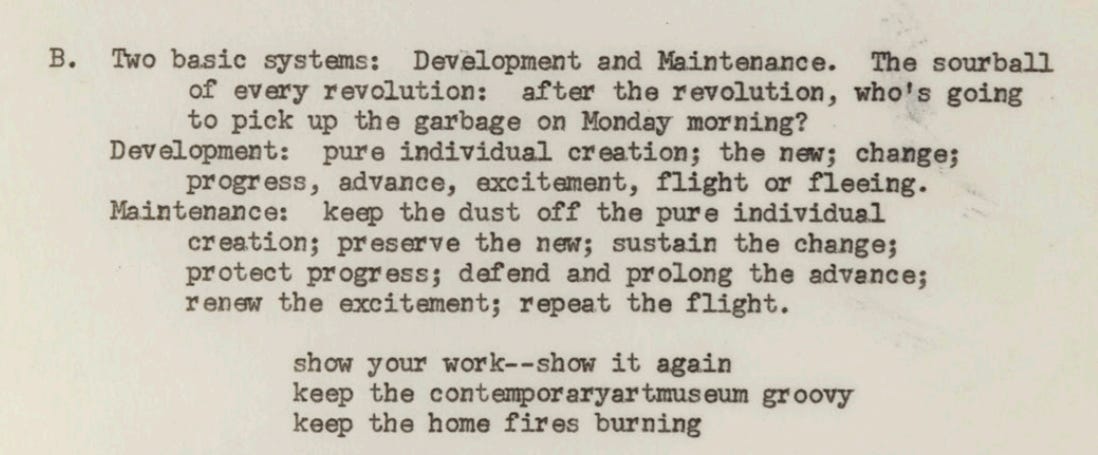

In her 1969 Manifesto for Maintenance Art, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles drew a clean line between: “development,” the high-status work of creation, and “maintenance,” the repetitive, sustaining work that keeps things alive.

“Two basic systems: Development and Maintenance. The sourball of every revolution: after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning? Development: pure individual creation; the new; change; progress, advance, excitement, flight or fleeing. Maintenance: keep the dust off the pure individual creation; preserve the new; sustain the change; protect progress; defend and prolong the advance; renew the excitement; repeat the flight.”

Maintenance, construction, and production aren’t glamorous. It doesn’t have a launch date or a press release. But it’s the reason I have electricity, listen to Bach, and type on a QWERTY keyboard.

Readings that inspired me:

Breakneck by Dan Wang

Simon Leys’s The Hall of Uselessness, which Dan Wang references in his book (mainly this essay)

1969 Manifesto for Maintenance Art, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles